The first book I read in 2022 was Brené Brown’s new Atlas of the Heart.

Essentially, this book is a catalogue of emotions, 87 in all. Its subtitle — ‘Mapping Meaningful Connection and the Language of Human Experience’ — perhaps gives a clue as to the intention behind it. For each of the emotions described, Brown typically devotes a page or two discussing the experience of that emotion and how it might be distinguished from other emotions that are related to it or for which it might be confused. Brown spends considerably more time on emotions in which she has devoted professional interest over the years, so shame in particular gets a very detailed examination.

Brown recounts that one of the prompts for writing the book was a survey she conducted in the course of her research into shame:

[W]e asked participants … to list all of the emotions that they could recognize and name as they were experiencing them. Over the course of five years, we collected these surveys from more than seven thousand people. The average number of emotions named across the surveys was three. The emotions were happy, sad, and angry.

I find this result extraordinary, and it really does paint a picture of a need for greater emotional literacy. Brown quotes philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein on this: ‘The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.’

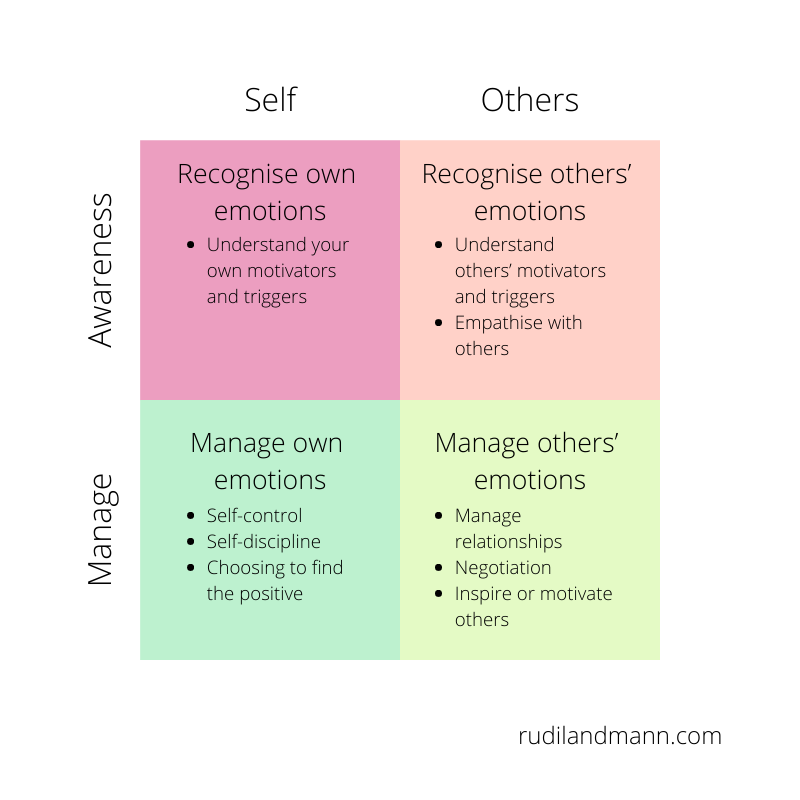

The need for this literacy seems to touch on a key finding from the growing field of Emotional Intelligence (EQ): that for most people, EQ can be trained, developed, and enhanced. More particularly, one of the most prevalent models of EQ (based on the work of Daniel Goleman) arranges different components of EQ along two axes: self-vs-others and awareness-vs-management:

Clearly, a book like this offers value to anyone who would like to build a deeper insight into their own emotions, or the emotions that they see in those around them. And Brown’s survey certainly suggests that there is a very great need for such insight.

But I’m also intrigued by two (big!) places that Brown doesn’t go in this book.

The first of these is considering how our understanding and experience of our own and others’ emotions intersects with factors such as culture, sex, gender, and sexuality. The closest she comes is consideration of how the culture of her own family shaped her emotional life, but she doesn’t discuss the relationship between this familial culture and Anglo-American culture more generally. By not discussing these intersections, I think that Brown’s book risks portraying one particular set of emotional experiences as the default and normal set for human beings.

The second is a lack of discussion around how our bodies respond to emotion, apart from a few scattered references to muscular tension and held breath. I think this is a really sad omission, particularly because such a main theme of the book is distinguishing between emotions that might be similar or at least appear superficially similar. A key element of somatics is that our emotions create physical reactions in our bodies, and therefore, by paying attention to our bodies we can more deeply discern our emotions. Instead of exploring this, Brown’s approach uses the conscious, rational mind as the only lens through which to examine and understand our emotions. To me, that’s a huge missed opportunity.

I’m definitely grateful to have this book as a resource; and my (digital) copy is heavily highlighted with a very large number of Brown’s interesting observations and well-put thoughts.

I’d recommend this book to anyone who is interested in how we talk about emotions (including to ourselves), and in particular to anybody who is currently working on developing the “awareness” quadrants of their own emotional intelligence or who is guiding someone else through that process.

Just mind the gaps.